The real world is a complicated place – our ideas about it, not so much. Yet we should always be smarter than our ideas!

Ideas exist within certain structural contexts, so called “mental models,” or frames of reference. It’s important to be able to look at these structures with an objective and critical eye. Advanced thinkers do just that.

Here’s a PRO TIP: Pay close attention to whether your frame of reference can be broken down by two’s or by three’s. Let’s take a look…

Pairs of Opposites

A lot of our core ideas come in pairs. These are often pairs of opposites. – Or they appear to be opposites because they are structured as pairs. – Consider the following examples:

BLACK WHITE

DAY NIGHT

WRONG RIGHT

GOOD EVIL

MANAGEMENT LABOR

LIBERAL CONSERVATIVE

CAPITALISM SOCIALISM

NOVICE EXPERT

These are fundamental concepts. Notice how each pair works to present a mental model that suggests a total system, a closed system. We call ideas presented in such a way “dualistic.”

There is nothing wrong with using pairs of opposites in everyday speech. Some practical matters are indeed as different as night and day. But dualistic thinking is problematic, due to its divisive structure. It tends to create antagonistic relationships between ideas, forces, groups, and agendas. Such models invite us to put everything we know into one bucket or the other. Dualistic thinking thus pulls us into what’s called a “zero-sum game.” – If one side of the equation is to win, that means the other side must lose. What benefits one is harmful to the other.

Sets of Three

On the other hand, ideas presented in sets of three create a very different dynamic. Think about these:

BLACK GREY WHITE

NOVICE ADVANCED EXPERT

POSITIVE NEUTRAL NEGATIVE

BODY MIND SOUL

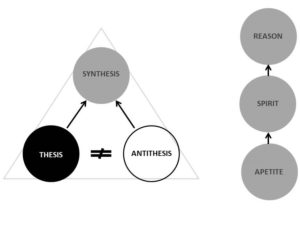

THESIS ANTITHESIS SYNTHESIS

EXCESS MODERATION ABSTINENCE

You get the idea. But your brain has to work a lot harder, doesn’t it! – Dualities are easy to grasp (thus politically useful). Ideas presented as sets of three, however, require advanced thinking. Such presentation of ideas is what we call “dialectical.”

Similar to the word “dialogue,” dialectical models are conversational rather than antagonistic. Where opposites are still employed, there is a third option. That option is either a combination of the opposites or a new category. Dialectical relationships help resolve or manage dualities by finding common ground. They can establish a value, or a range of values, between extremes. Dialectical thinking lends itself to “non-zero-sum” games. There needn’t be a winner or a loser. The relationship of the ideas remains open ended.

Use of Dialectical Models

We may use dialectical models to construct hierarchies. For Hegel, the synthesis is always superior to both the thesis (an argument) and its antithesis (the opposing view). But this supposes that a dialogue has occurred, where the errors of each opposing side in an argument have been culled out and working consensus has been established. – See the previous article, Philosophical Bullsh*t? for more on this process. – In his Republic, Plato makes a case for thinking about the human psyche with a dialectical model. There are within each of us Reason, Spirit, and Appetite. While Plato does think that Reason should be in charge of things, that does not negate the other elements. The whole system thrives when properly ordered.

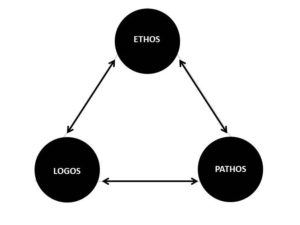

But conveying a hierarchy need not be the outcome. From Aristotle we learn what is now referred to as the “Art of Persuasion” (or Rhetoric). Effective persuasion relies on the dialectic between Logos (logic), Pathos (emotion), and Ethos (the credibility of our behavior). In this model each element is equal to the others, at all times. Success comes from tapping into and demonstrating all three!

Conclusion

When we talk about mental models, we mean to say that our ideas represent reality in a simplified form. No model is perfect or in fact comprehensive. Dualistic models have their place in our mental tool box, but they tend to over simplify reality. And they tend to be both antagonistic and static. They leave us with either/or and win/lose propositions. – Dialectical models are more open ended and fluid. They present us with alternatives. They offer us win/win propositions. It is not just this or that. It may be a bit of both or something else entirely. They invite discussion. They give us a path toward resolving conflicts. They set us on a path that doesn’t involve crushing or discrediting our opposition.

Now you won’t always find the landscape of ideas so tidy. Dualities can be hidden in quantities of four or six, and so on. Consider a survey question that asks whether you “Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Agree, or Strongly Agree.” While allowing for gradation, this is still dualistic. Mind you, there is nothing underhanded about it. The surveyor wants to elicit an emotional response. Here neutrality isn’t an option. – Likewise, dialectical models can appear in sets of five, seven, or what have you.

Even or odd, you can look for these underlying structures as a ready analytical tool. Watch for clues when you listen to the news or hear a persuasive argument. When you are reflecting on your own views or learning a new idea, you can ask yourself:

- Am I being asked to buy-in to a dualistic system?

- Are my ideas emotionally charged with an Us vs. Them, Good Guys vs. Bad Guys, mentality?

- Can I break a complex set of ideas down to five or three main categories?

- Am I nurturing all the important elements of my life or is one aspect prioritized at the expense of the others?

- Can I find a workable consensus with someone I disagree with?

Advanced thinkers examine thought processes and mental models with a critical eye. Don’t allow yourself to be duped into a simplistic view or to get stuck. Think for yourself and challenge even your own thinking. Be smarter than your ideas!

Your comments and feedback are important! Please see the Table-13 Code of Conduct before leaving a reply. All comments are moderated.